- Start Exploring

- Why the BibleAnswering your questions about the Bible

- Get a BibleFind the Bible that's just right for you.

- Read the BibleThe story of the Bible and tools to study it.

- Know the BibleResources to help you understand it.

- Live the BibleHelping you live out a biblical worldview.

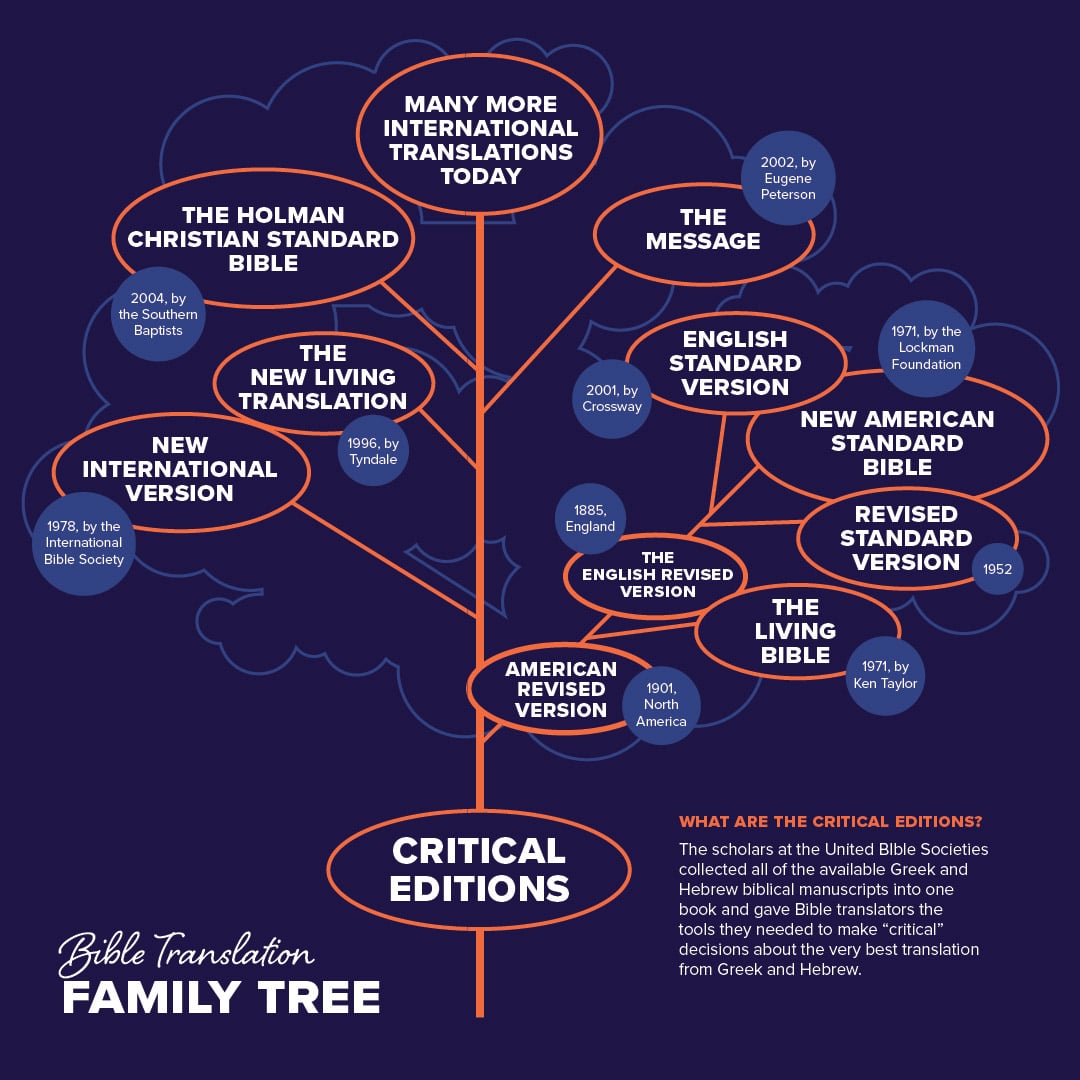

Why the BibleAnswering your questions about the BibleQuestionsArticlesThe Bible and...Get a BibleFind the Bible that's just right for you.Find a BibleLearn About TranslationsAudio Bible AppsRead the BibleThe story of the Bible and tools to study it.Read the Bible as a FamilyOverviewRead the BibleStudy the BibleDiscover resources that will encourage and equip you to engage with the Bible with the loved ones in your home.

Know the BibleResources to help you understand it.Biblical WorldviewPopular VersesHymnsCreeds & CatechismsLive the BibleHelping you live out a biblical worldview.People of FaithFollowing JesusLife ChallengesTestimonies

- Questions

- The Big Questions

- Ask a Question

The Big QuestionsThe BibleGodJesusAsk a QuestionContact UsFaith Questions?What questions do you have?

Contact us and one of our team

members will personally respond

to you by email.Have questions about your relationship

with God? Start a conversation with one

of our responders who is ready and

willing to answer your questions.

- Topics

- The Bible

- Biblical Worldview

- Life Challenges

- Historic Works

The BibleIs it God's Word?Is It Reliable?How to Read ItHow to Apply ItKey PassagesOn LoveOn God's WillOn Fear and AnxietyAll things work together….

Count it all joy……

For I know the plans…

The Lord is my shepherd…

Do not be conformed…

I can do all things…

Do not be anxious…

Seek first…

Cast all your anxiety…

Fear not, for I am with you…

Be strong and courageous…

Whoever dwells in the shelter…

Biblical WorldviewGodSinJesusSalvationPrayerHoly SpiritFollowing JesusAfterlifeLife ChallengesEmotionalRelationalPhysicalAddictionsOld TestamentNew TestamentBiblical PeopleMen of FaithWomen of FaithContemporaryHistoric Works

- Articles

- Podcasts